Soundscape Ecology

Soundscape ecology can be defined as the study of all biological, geophysical, and human-produced sounds in a landscape and how those sounds interact the ecological community across different scales.

Raymond Murray Schafer was the first to use the term “soundscape” which he described as “the acoustical characteristics of an area that reflect natural processes”, and can be understood as all sounds coming from a given landscape. Soundscape ecologist Bernie Krause later created the categories of biophony, geophony, and anthrophony to help distingiush types of sound that can be heard in a given environment (Pijanowski et al.).

Biophony refers to sounds produced by living things in an environment, which includes the bird calls we’ll be listening to here! Anthrophony is sound made by humans, from machinery and automobiles to singing and speaking. Geophony is the nonbiological sounds of an environment including those made by weather such as rain or lightning, as well as bodies of water and even cracking of the Earth’s crust.

These categories are useful tools to help us listen more critically to our surroundings, however they are not distinct boundaries and sounds can exist that don’t fit clearly into one of them. Additionally, the separation of sounds and, by extension, their sources can be problematic in the way that we view ourselves in relation to the environment around us.

The Issue with Separation – Biophony vs. Anthrophony

Our dominant social paradigm reflects the overwhelming human-centeredness of our society and a lack of connection between people and non-humans in the landscapes around us. This disconnect has negative implications for how we care about and for our environment, in a world where climate change and human land use increasingly threaten the existence of ecosystems and species across the planet.

People are more likely to care about saving or protecting something if they are familiar with it, and we can use sound as a tool for strengthening our connection to the species that we are surrounded by. Our perception of biophonic sounds around us often puts them into broad “other”, or non-human, category rather than being tuned into what is really going on and what organisms we are interacting with. Listening for bird calls in our everyday life is an accessible way to increase our sonic awareness and learning to hear distinctions within that sound pushes back against the idea of humans as above and separate from the other living things around us.

Indigenous Epistemologies

Steven Feld’s work with the Bosavi people in Papua New Guinea brings to light how the Bosavi know their world through sound, and particularly their interactions with birds. Bosavi song mirrors the sounds of birds and rivers in the rainforest and can be described as poetic cartography because of how their song ‘paths’ follow a physical path in the environment and capture space and sound (Feld 2003). Bosavi songs are oftentimes mappings of the rainforest from a bird’s point of view and include acoustic materials from birds in their local environment including intervals and rhythms (Feld 2015). Their spiritual connectedness with birds extends to a sonic interaction that revolves around sound-making from both the birds and people. Indigenous epistemologies, or ways of knowing, include a deep connectedness with the local environment and extends to sound in many ways. Much like Bosavi songs, music that is part of Tuvan shamanism comes from imitation of sounds in nature, from animals to rivers (Levin). This awareness of sounds in a place creates a deepened relationship between an individual and the surrounding landscape.

Learning to Listen

Featured below are four commonly heard birds in Northeastern Ohio, the northern cardinal, blue jay, downy woodpecker, and mourning dove. We can use photos to help us recognize a species, but will focus on characteristics of their calls in order to build familiarity with these birds as a way of building sonic awareness. By learning to identify birds by their calls and sounds we can shift towards a way of knowing our environment that includes sonic observation rather than sight alone.

Northern Cardinal – Cardinalis cardinalis

The northern cardinal is a commonly seen and heard songbird in Northeast Ohio and much of the Eastern United States. Its bright red coloring might let us identify it easily by sight, but we can also locate a northern cardinal by listening for its cheery, fast calls.

Cornell’s Lab of Ornithology has countless resources for birding and identifying species. Their eBird platform lets you look at population density based on user data, as well as many different audio files, photos, and videos from different areas (linked below).

Blue Jay – Cyanocitta cristata

The recording on the left is an example of the commonly heard alarm call of a blue jay.

Blue jays are known to mimic the sounds of hawks and other birds of prey, the recording on the right is of a blue jay mimicking a bald eagle (Blue Jay Overview).

Another valuable tool for learning about the bird species we find is Cornell Lab’s All About Birds site, which has comprehensive ID, range, and habitat information, as well as facts about their behavior.

Blue Jay Overview – All About Birds

The site references migration behavior which may be observed in our area of Ohio “Thousands of Blue Jays migrate in flocks along the Great Lakes and Atlantic coasts, but much about their migration remains a mystery. Some are present throughout winter in all parts of their range” (Blue Jay Overview).

Downy Woodpecker – Dryobates pubescens

The most recognizable sound of a woodpecker is the drumming that comes from their pecking on tree trunks in search of insects, shown below (Downy Woodpecker Identification). Downy woodpeckers are the most common woodpeckers in Ohio (Gazso). You may hear a this tapping sound and look around to find one of these small birds hopping along a nearby tree, or flying in their distinctive rise and fall pattern as they drop between wingstrokes.

The recording on the left below exemplifies the repetitive tapping sound of a downy woodpecker.

On the right is an example of the short, shrill call of a male downy woodpecker.

Mourning Dove – Zenaida macroura

The mourning dove has a soft and oftentimes nostalgic cooing call, and is one that is harder to spot, encouraging the use of sound to notice and locate one.

This clip is of an adult male from a perch at the top of an oak tree, demonstrating the “song” or “perch-coo” that is made by unmated male mourning doves from a perch. It can be recognized by a soft coo-oo with two or three louder coos following it. A different call can be heard coming from paired males during nest-building, a coo-OO-oo with the highest pitch in the middle (Mourning Dove Sounds).

Listening Practice

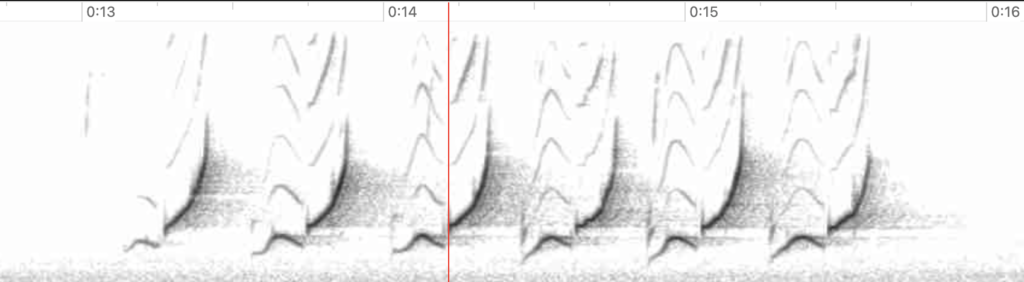

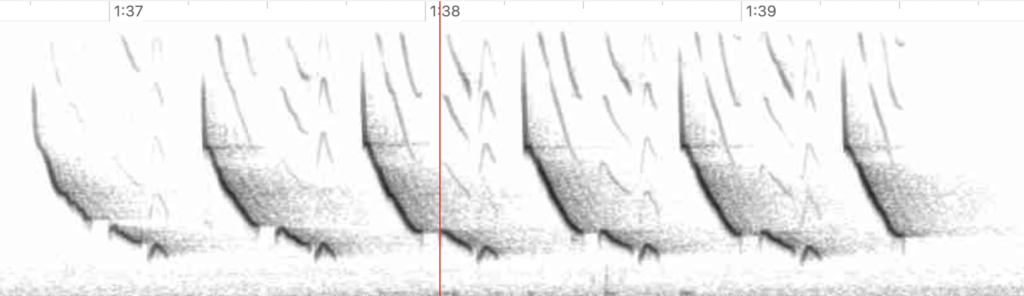

Now let’s listen to some bird calls in the context of a more dense soundscape! This recording was taken at the Oberlin Arboretum in early fall and has a prominent bird species among the layers of biophony, anthrophony, and geophony.

You should be able to hear the screech-like calls of blue jays!

Building a critical ear to listen for birds in our daily life is a powerful tool for increasing sonic awareness and connectedness to the landscapes around us. This adds to our sense of place in our environments and encourages us to notice and care about the non-humans in the places we call home that are increasingly important to recognize.

Bird Song Identification Resources:

All About Birds – Cornell Lab of Ornithology

Links to embedded photos and audio files (if not loading):

References

“Blue Jay Overview, All about Birds, Cornell Lab of Ornithology.” Overview, All About Birds, Cornell Lab of Ornithology, www.allaboutbirds.org/guide/Blue_Jay/overview#. Accessed 5 Jan. 2024.

“Downy Woodpecker Identification, All about Birds, Cornell Lab of Ornithology.” , All About Birds, Cornell Lab of Ornithology, www.allaboutbirds.org/guide/Downy_Woodpecker/id. Accessed 5 Jan. 2024.

Feld, Steve. 2003. “Rainforest Acoustemology” in The Auditory Culture Reader, edited by Michael Bull and Les Back. Oxford, U.K.; New York, N.Y.: Berg. 223-239.

Feld, Steve. 2015. “Acoustemology” Keywords in Sound Duke Univ. Press, ed. David Novak (OC ‘97) and Matt Sakakeeny. 12-21

Gazso, Tony. “Woodpeckers of Ohio.” Lake Metroparks, 1 Aug. 2022, www.lakemetroparks.com/birding-blog/february-2021/woodpeckers-of-ohio.

Levin, Ted. 2006. Excerpts. Where Rivers and Mountains Sing: Sound, Music, and Nomadism in Tuva and Beyond. Bloomington: Indiana University Press.

“Mourning Dove Sounds.” All About Birds, Cornell Lab of Ornithology, www.allaboutbirds.org/guide/Mourning_Dove/sounds. Accessed 5 Jan. 2024.

Pijanowski, Bryan C., et al. “Soundscape ecology: The science of sound in the landscape.” BioScience, vol. 61, no. 3, Mar. 2011, pp. 203–216, https://doi.org/10.1525/bio.2011.61.3.6.

Scott. “35 Most Common Birds in Ohio! (2024).” Bird Watching HQ, 2 Nov. 2023, birdwatchinghq.com/common-birds-in-ohio/.

I have adhered to the Honor Code in this assignment. – Natalie Dresdner