History

In the 1930s, large-scale marimba orchestras were on the rise. in 1933, the Century of Progress Internation Exhibition in Chicago featured a marimba orchestra comproised of 100 players, conducted by Clair Omar Musser. Not only had Musser conducted this ensemble, but he designed the marimbas they were playing as well, titled the “Century of Progress Model” of marimbas. They were manufactured by J.C. Deagan, a company named after its founder, John Calhoun Deagan.

In 1934, Musser began to organize another 100-piece marimba orchestra comprised of 50 men and 50 women, titled the International Marimba Symphony Orchestra (IMSO). The marimbas he designed for this are known as the “King George Model.” Musser auditioned every musician, arranged the music himself, and coordinated all rehearsals. He made 102 of these marimbas. 100 for the ensemble, one for Musser himself, and one for King George V of England. There were three versions of the marimba, all with the model “IMSO.” The most common was the four-octave, F to F version. Less common was the four-octave, C to C version, which Oberlin has. Only 2 bass marimbas were made. It is also worth noting that one King George model vibraphone was hand crafted for Lionel Hampton, world renowned jazz vibraphonist and pianist.

Each King George marimba was designed for a specific person. These musicians were mostly teenagers that Musser taught and auditioned himself. The name of each individual is on each King George marimba, in a traiditional British coat-of-arms. Oberlin’s King George was made for Carl Robert Bailey. One was made for Bailey’s brother as well, which was almost purchased by Oberlin, but never went through. As for who Carl Bailey is, we don’t know. He and many of the other musicians from the IMSO have been lost to time.

Unfortunately for Musser, the IMSO never made it to England, and neither did the marimbas. The American musician’s union had prevented English musicians from playing in the united states. In retaliation, the English muscian’s union prevent Americans from playing in England. Because of this, the concert planned for King George never happened, and the orchestra eventually sailed to France instead.

Shortly after World War II, Musser left Deagan, and went on to start his own company, Musser, which is still around to this day. Oberlin owns two Musser “Brentwood” marimbas, and a Musser vibraphone. Oberlin also owns several Deagan xylophones, chimes, and glockenspiels.

Oberlin’s King George

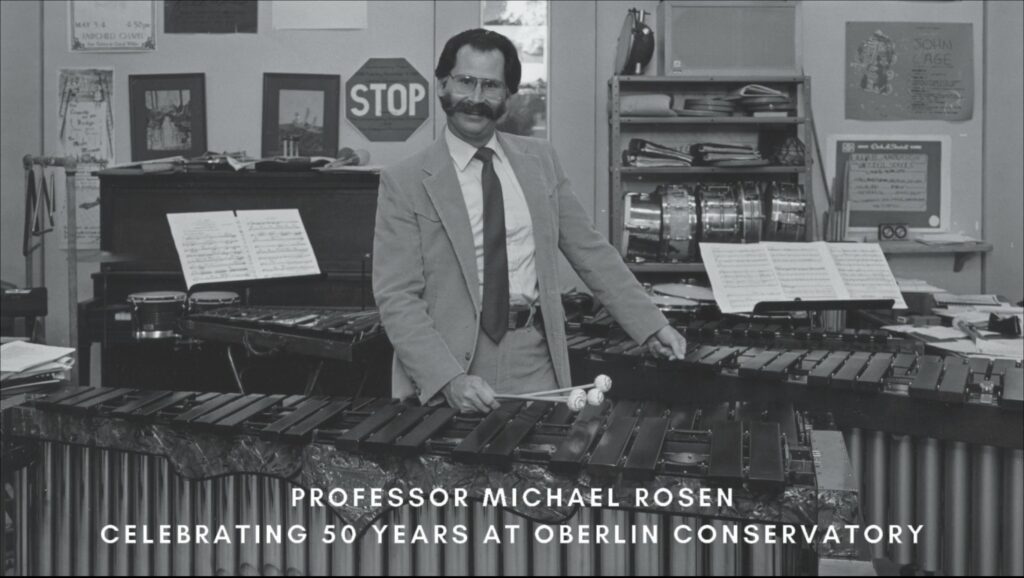

Oberlin’s King George was purchased by former percussion teacher Michael Rosen in Southern Ohio for around $1700 in the 1970s. Adjusting for inflation, that’s around $5000 in today’s money. Along with our King George came the original cases, which are even rarer than the instrument itself.

Shortly after purchasing the marimba, Michael Rosen moved the cases to the basement of Bibbins. In 1989, the conservatory built the TIMARA labs in the basement of Bibbins, and the King George cases stored there were lost. For over three dacades, Michael Rosen searched for the cases. In Spring 2021, Michael Rosen found one of the several cases in the basement of Robertson, in a mildewed, rotting state.

On our instrument, in the highest two octaves, the F#, G#, C#, and several other notes have dents in them. It’s worth noting these are the primary notes played in the most common xylophone excerpt, Porgy and Bess. Michael Rosen believes that someone at some point on this instrument was practicing Porgy and Bess with too hard of mallets, and dented the bars.

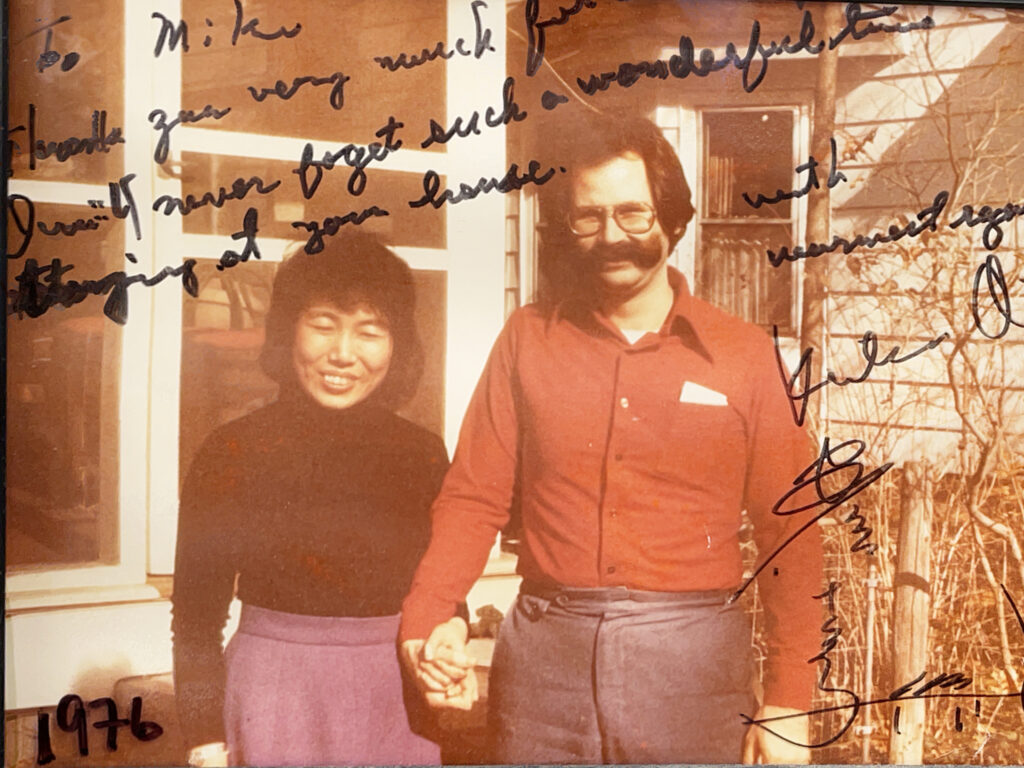

Keiko Abe

In 1976, internationally renowned marimba player Keiko Abe visited America for the first time from Japan. Along with her, she brought her translator, and a man who’s specialty was musical acoustics and tuning pitched percussion instruments. Not only did she bring those two people, but she also brought a whole new genre of marimba playing with her. Michael Rosen was the primary reason why she visited, and he helped her tremendously in her time here. Because of this, Michael Rosen is known as “The man who brought Japanese Marimba to America.”

During her time here, she took a strong liking to Oberlin’s King George Marimba. She and Michael Rosen noted its dark sound. Her tuner analyzed the sound produced from the King George and noticed a strong minor 3rd overtone, highly unusual of any marimba. Most modern marimbas have a major 3rd overtone.

During a performance of Minoru Miki’s Time for Marimba, Keiko Abe cracked the low C on Oberlin’s King George Marimba. Her tuner took the measurements of the bar, went back to Japan, tuned it to the best of his ability to match the harmonic spectra of the instrument, and sent us a replacement bar, which is still curently on this instrument. Notably, it is brighter colored than the other bars on the instrument.

Yamaha and Oberlin’s King George

The tuner who visited Oberlin and replaced the low C, through conversations with Michael Rosen and Keiko Abe, decided to try to make a 5-octave equivalent of the King George, using the harmonic spectra of our instrument. Around this time, Yamaha started making marimbas (which they still do to this day, including the Keiko Abe marimba). Yamaha, in collaboration with the tuner who visited Oberlin, manufactured a 5-octave version of the King George, and brought it to the annual Percussive Arts Society International Convention (PASIC) in the Untied States sometime in the 1980s.

Unfortunately, many percussionists at the convention, including Michael Rosen and Keiko Abe, noted it sounded nothing like the original King George Marimbas. The consensus was that the 5-octave version would have to have different bar lengths and widths to get the original minor-3rd overtone, which would mean Yamaha would have to change their entire assembly line. Unfortunately, Yamaha was not willing to do this due to costs, and consequently, Yamaha took the bars back to Japan, where they were llikely cut down and used to make other instruments.

Restoration of our King George

Sometime in the 90s, Michael Rosen took the instrument to a company in Cleveland known for polishing trumpets and trombones, where he asked them to polish the brass end posts, and resonators. Because the resonators weighed significanlty more than any trombone or trumpet, the company only polished the front row of resonators, since they took three people to hold up for an extended period of time up to the buffing wheel. They said they would never do this again for us.

Gordon Stout

Gordon Stout (b. 1952), American percussionist, composer, and teacher, visited Oberlin conservatory and brought his King George marimba with him. He played his own work,Two Mexican Dances, in a recital with Michael Rosen, featuring both his King George and our King George. He noted that ours sounded better than his.

Oberlin’s King George in the present-day

Due to issues with excess moisture in Central 38 (the percussion studio), the brass resonators have slowly detiorated over the years. When Michael Rosen retired in 2021, he officially donated the marimba to Oberlin Conservatory, and the King George was moved to the basement of Kohl, in the percussion storage room, where it spends most of its time now. It is almost exclusively used for performances now.

Oberlin’s King George marimba was mostly recently performed on in the Oberlin Percussion Group (OPG) Festive Holiday Event on December 13th, 2023 at 4:30 PM (by me).

Materials of the King George Marimba

There are several components to making a King George marimba. The resonators are made of brass, which eventually lost favor in pitched percussion for the lightweight, similar sounding aluminum. The end posts do feature three slots for the resonators to rest in of various heights. These are called “temperature height adjustments.” The front of the marimba is black painted wood with a silver marbleized finish. The bars were suspended originally with maroon cord, which broke easily. Our King George’s bars are suspended with green paracord. Lastly, the padding underneath the bars is made of velvet.

Rosewood

Rosewood, a type of tropical hardwood is the type of wood used for the bars on these instruments, as is the case with the vast majority of modern marimbas across the world. Other tropical hardwoods include ebony and mahogany. It is worth noting that rosewood for percussion instruments was in fact standardized by John Calhoun Deagan himself. It is unknown where exactly Deagan sourced his rosewood from, though rosewood generally grows in central America.

One of the only modern percussion companies that discloses the location of where they source rosewood from is Marimba One, which sources their rosewood sustainably from a community in Belize. Most percussion companies do not have any publicly available information about their rosewood sources.

Rosewood, among other tropical hardwoods is incredibly endangered. Rosewood is native to Brazil, Honduras, Jamaica, Africa, and India. Honduras rosewood, Dalbergia stevensoni, is the most commonly used in percussion instruments.

The Convention on International Trade of Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora (CITES) is an international agreement between governments. Over 29,000 plant species are protected by CITES. In 2017, the entire rosewood genus was added to CITES, specifically to combat the rosewood furniture trade. This also led to the trade of rosewood instruments to be banned unintentionally. In 2019, CITES was revised and exempted rosewood musical instruments, allowing them to be traded again.

Rosewood alternatives

Several alternatives exist for rosewood in marimbas specifically. One of the most common is Padauk, used by Adams, Bergerault, Korogi, Musser, Malletech, DeMorrow, Marimba One, and Yamaha, among others. The next most common alternative is synthetic bars. Companies that produce synthetic marimbas include, Adams, Majestic, Yamaha, Mode, and Musser. Mode also creates fully electronic marimbas. Generally, rosewood is more expensive than the alternatives, and the general consensus is it sounds and feels better to play.

J.C. Deagan

John Deagan did more than just standardize rosewood for percussion instruments. In fact, he’s the man responsible for A=400 being the standard universal pitch for orchestras and bands. He was a member of the American Federation of Musicians, and persuaded them to adopt this policy in 1910. Other achievements include being a nationally recognized clarinet player and designing the first scientifically tuned glockenspiel in 1880.

Deagan died in 1934. His daughter-in-law, Ella Deagan, led the company after his death. In 1978, Deagan was purchased by Slingerland. In 1984, Deagan was sold to the Sanlar Corporation. Today, Deagan instruments are manufactured by Yamaha. Many chimes and tower bells across the world were manufactured by Deagan, including the chimes that were in the original organ in Finney Chapel (which are now stored in the basement of Kohl). Those chimes and towel bells continue to ring across the world in many churches and organs.

Acknowledgements

I could not have done this without the help of my teacher, Michael Rosen, who helped me tremendously through this project, and also my percussion career. Additionally, my current teachers Ross Karre and Jennifer Fraser, who helped brainstorm and guide me throughout this project.

Works Cited

Errede, Steven. Lecture Notes For UIUC Physics 193 POM Physics of Music/Musical Instruments: “Sustainability and Musical Instruments” Department of Physics, University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, Illinois. 2002 – 2013.

Greenberg, James B. 2016. “Good Vibrations, Strings Attached: The Political Ecology of the Guitar” Sociology and Anthropology 4(5):431-438.

United Nations Environment Programme. 2010. Singing to a Greener Tune. Current status of the music industry in addressing environmental sustainability. Report prepared by Meegan Jones and Xenya Scanlon, Music & Environment Initiative, UNEP. March 2010.

Britannica, The Editors of Encyclopaedia. “Fabaceae”. Encyclopedia Britannica, 1 Nov. 2023, https://www.britannica.com/plant/Fabaceae. Accessed 16 December 2023.

“King George Marimba Object Record.” 1993.01.01 – Marimba, Percussive Arts Society, rhythmdiscoverycenter.pastperfectonline.com/webobject/1CC918CE-653D-4FF3-A3BD-075704276843. Accessed 16 Dec. 2023.

“King George.” The Deagan Resource, deaganresource.com/imso.html. Accessed 16 Dec. 2023.

Lucke, Jonathan D, and Michael Rosen. “Oberlin’s King George Marimba.” 13 Dec. 2023.