Dead Tree Instruments: Sustainable Material Use in Instrument Building

Within the conservatory environment, and the larger sphere of music education, the ephemeral arts of performance are kept separate from the material practices of instrument building. This disconnect between sound and material results in a lack of knowledge about the physical labor of making, the material histories of musical instruments, and their environmental impact (Smith 571). Reinforcing consumerist ideologies, this separation is representative of our disjointed contemporary western relationship with the surrounding landscape, and perspectives of entitlement towards land and natural resources. Indigenous philosophies of land use are a rich source of lived and practiced knowledge about how to maintain a healthier and more symbiotic relationship to the landscape through listening (Hamill 118). These philosophies of interconnectedness are relevant within the discipline of instrument building, as we reconsider methodologies of resource extraction and search for alternatives to endangered materials and unethical labor, attempting to find a more sustainable way to create new instruments (Errede 6).

The Instruments:

On Saturday December 9th 2023, I presented an installation and performance in the nature preserve behind the George Jones Memorial Farm. As part of this installation, I created five zithers built directly onto dead trees, utilizing the tree body as the resonant structure for sound production. One of my intentions with this piece was to reconnect the material histories of the instruments with the more ephemeral experience of performance, to present the continuity between sound and the physical body of the instrument. Rather than harvesting and removing materials, I worked with what was there and built directly on the site. The process of building and creating was therefore also a process of observation and learning, as I walked around knocking on dead trees, searching for natural resonance within the wood.

As I mounted the strings and began experimenting with how to play these new instruments, I noticed the variation in timbre created by each dead tree, and the individuality of their sonic properties. While some trees had almost no natural resonance, others were incredibly loud and bright without any amplification. One tree I utilized had been hollowed out by woodpeckers, and when a string was plucked it would sustain a continuous sound. The uneven topography of the surface of the trees also created some beautiful overtones, as the vibrating strings would brush against these uneven surfaces. The instruments held their pitch surprisingly well despite temperature and humidity changes. My final decisions about tuning the tree instruments were made to maximize the open resonance of the sound. I referenced hardanger fiddle tunings and tuned each tree slightly differently, though each had either an open A or D string. In this way, I worked with the material properties of the dead trees, allowing for push and pull while staying open to the material within the creative process of building these instruments. Through working on site and using found materials, I was able to build instruments that exist largely outside the market of global trade (Greenberg 437).

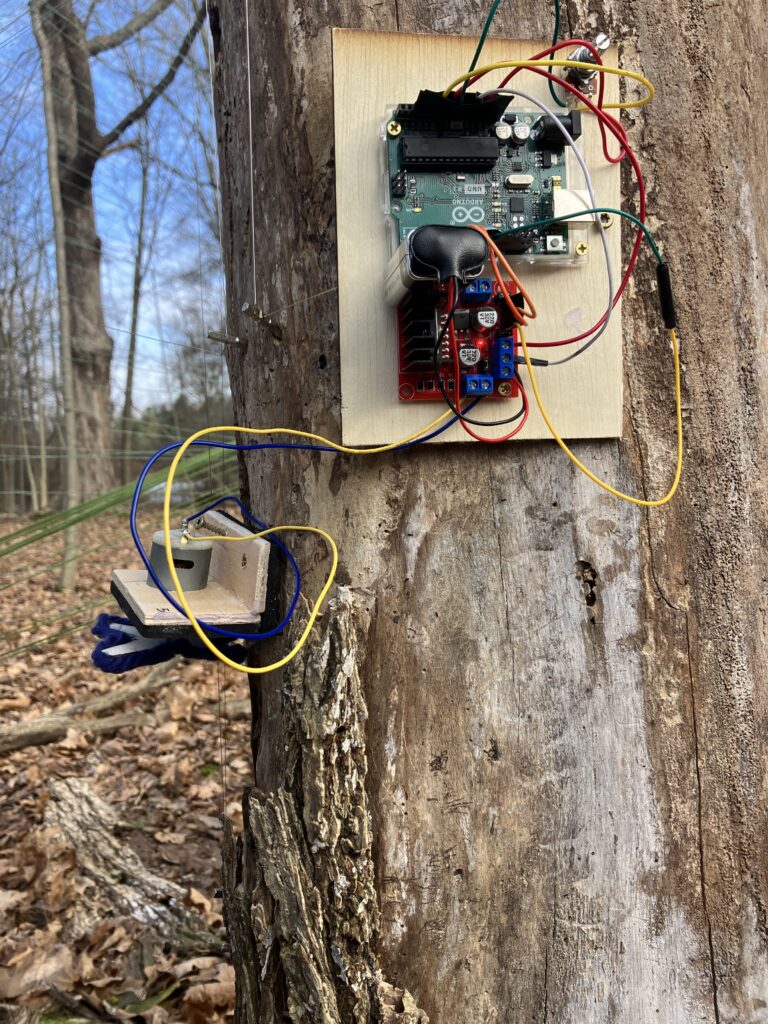

< Tree motor circuits

^ Early experiments, playing the trees

The Performance and Scoring:

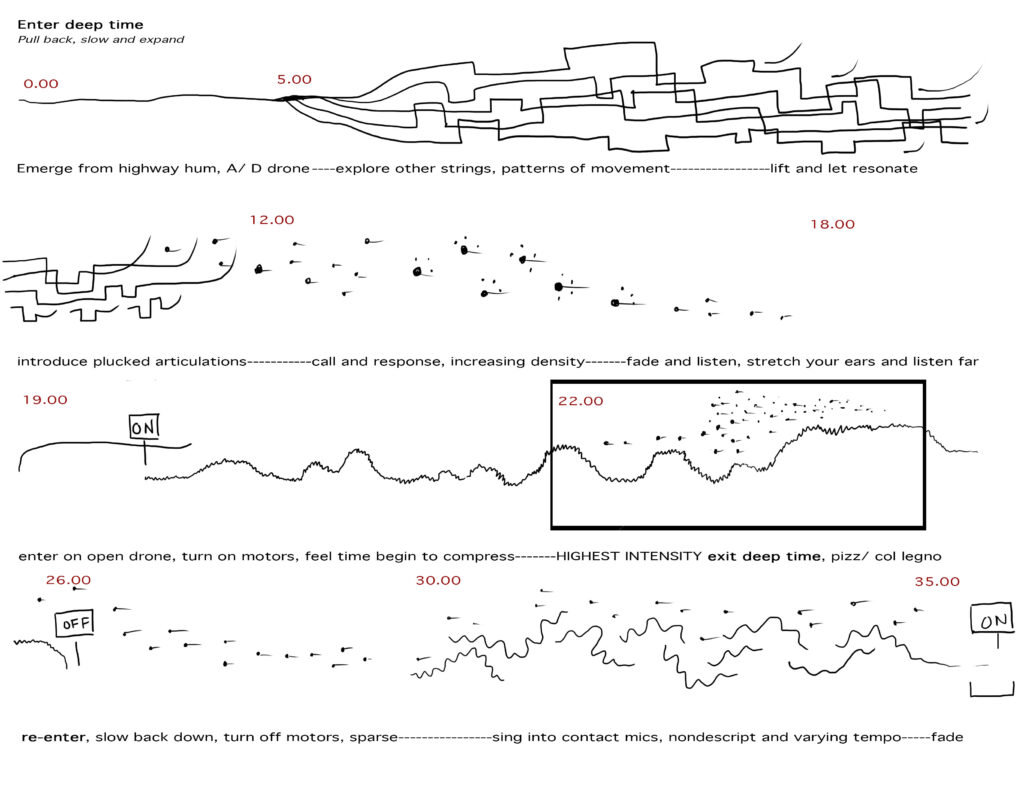

Within the live performance of the piece and the written score, I considered and embraced the woodland soundscape that was already present in the sonic environment. In “The Earth Is (Still) Our Mother: Traversing Indigenous Landscapes through Sacred Geographies of Song’, Hamill describes how indigenous song is a product of the landscape, and therefore the destruction of the landscape by settlers has historically resulted in the cultural destruction of song and stories (115). While creating the performance, I thought about this indigenous interconnectedness between song and place. Within Bosavi musical tradition, for example, song is used to map the geography of a landscape and the people within (Feld 227). Therefore the 35 minute piece I wrote for these dead tree instruments directs the performers to open their ears and “enter deep time”, to slow down and to listen. It asks them to imagine life beyond the scale of the performance, understanding this moment as only a tiny blip within the story of this landscape. The score integrates moments of sparsity or even silence, allowing environmental sounds to rise to the forefront.

There are many aspects of working and performing outside that are unpredictable, and on December 9th, the day of the performance, this unpredictability came in the form of rain. The rain transformed the soundscape and molded the performance experience in many ways. I protected the technology the best I could, which mostly consisted of amplifiers and motor control circuits, and did my best to embrace the rain. This nighttime, warm December rain seemed to create a more somber and emotionally charged atmosphere. After the performance, I received numerous positive comments about how the rain expanded the experience of the piece, and how the piece as a whole created space for viewers to embrace being in these conditions. At the beginning of the piece, the rain was coming down hardest as the performers were playing a continuous drone, but as the rain lightened, the performers shifted to sparser, plucked articulations. While not intentional, unpredictable and surprising moments such as these felt somewhat magical in the space of the performance.

Within the writing of this piece and the building of these dead tree instruments, I applied our in-class discussions about material sustainability and indigenous epistemologies of connectedness between the body and the landscape. This approach can be most clearly exemplified within the final section of the piece, in which I had the performers sing fragments of a folk song called “The Wind and Rain”. I directed the performers sing directly into the tree, amplifying the sounds of their voices through mounted contact mics. The lyrics of this song, which describe the body of a young woman being made into a violin, alongside its presentation within the context of the piece, relate back to indigenous epistemologies of continuity between land, body, and song (Galloway 123).

.

Performance Documentation

Bibliography:

Allen, Aaron S. 2023. “Ecoorganology: Towards the Ecological Study of Musical Instruments”. Sound, Ecologies, Musics. Edited by Aaron S. Allen and Jeff Todd Titon. Oxford University Press. 17-40.

Errede, Steven. Lecture Notes For UIUC Physics 193 POM Physics of Music/Musical Instruments: “Sustainability and Musical Instruments” Department of Physics, University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, Illinois. 2002 – 2013. All rights reserved.

Feld, Steve. 2003. “A Rainforest Acoustemology”. The Auditory Culture Reader. Edited by Michael Bull and Les Back. Oxford, U.K.; New York, N.Y.: Berg. 223-239.

Galloway, Kate. 2020. “The Aurality of Pipeline Politics and Listening for Nacreous Clouds: Voicing Indigenous Ecological Knowledge in Tanya Tagaq’s Animism and Retribution.” Popular Music 39 (1): 121–44. https://doi.org/10.1017/S026114301900059X.

Greenberg, James B. 2016. “Good Vibrations, Strings Attached: The Political Ecology of the Guitar.” Sociology and Anthropology 4(5):431-438.

Hamill, Chad (čnaq’ymi). 2021. “The Earth Is (Still) Our Mother: Traversing Indigenous Landscapes through Sacred Geographies of Song”. Transforming Ethnomusicology, Vol II. Edited by Beverley Diamond and Salwa Shawan Castelo Branco, Oxford University Press.

Smith, Alex. 2018. “Reconnecting the music-making experience through musician efforts in instrument craft.” International Journal of Music Education,36(4), 560-573. https://doi.org/10.1177/0255761418771993